SEATED BESIDE

Perhaps more than anyone she would be well placed with anyone on the table. Some she will know well, some less so. Almost the youngest on this top table. We await inspiration. One DinnerPuzzle reader has suggested she may well have got on well with Stephen Gwynn, the Irish writer and contributor to Time and Tide.

WHAT’S ON HER MIND?

Ready to discuss anything, whilst on this evening probably wanting to ensure her mother Alice is well seated and can relax a little after the difficult time they will have had since the death of her father at the beginning of the month. Like her mother she will undoubtedly be receiving condolences from many friends. It is quite likely that she got to meet the South African writer Sarah Millin for the first time at the dinner.

WINIFRED’S STORY SO FAR

Winifred Holtby was born at Rudston House in Yorkshire on 23rd June 1898, the penultimate Midsummer’s Eve of the 19th century (to put it more lyrically) to Alice Holtby née Winn, a farmer’s daughter and David Holtby, a prosperous Yorkshire farmer of 940 acres (that would have been roughly twice the size of a typical wold estate). Or when, if the imaginative testament of Vera Brittain is reliable, “the young fields of grass, wheat, oats and barley turned the patchwork of the wolds to its vividest green, brilliant against the purple of the dark earth which the grain had not yet pierced”.[2]

Winifred was educated at home by a governess, before going to Queen Margaret’s School in Scarborough, and then on to Somerville Oxford – though in 1932 she wrote to Sarah Gertrude Millin, the South African novelist seated on Vera’s table at our dinner, that if a sympathetic schoolmistress had not persuaded her parents to send her to college, she would never have left that environment of animals, seasons, shooting parties, the visits of foremen and pig dealers, the calls of millers and their wives.[3] In fact she went to Oxford in 1917, lasting a year before getting permission to go up to London on the pretext of visiting a relative and promptly joining the Queen Mary Army Auxiliary Corps – someone driven to make her contribution to the war effort.

Once across the Channel Winifred was assigned to a signals unit at the Chateau d’Huchenneville, near Abbeville, in part because one Jean Findlay McWilliam, the South African administrator there, heard there was a fellow Somervillian available and welcomed the company. On introducing the rudimentary facilities Jean commented that even “Rosalind and Celia had difficulty getting baths in the Forest of Arden”. The two contrasting women in Shakespeare’s As You Like It became their names, if not personas, in their later correspondence between South Africa and England, published in “Letters to a Friend” after Winifred’s premature death in 1935 – correspondence which, alongside Vera’s Testimony of Friendship – The Story of Winifred Holtby, provides a rather special form of biography.

In fact the correspondence of Rosalind and Celia has itself helped to inspire this website project: as I began researching the four columns of largely unknown people on the guest list I realised that amongst the books left to me by my maternal aunt (and daughter of my grandfather J.T. Rhys) was her copy of “Letters to a Friend” and virtually as soon as I had opened it – for the first time I confess – (and there is no index so no cheating there) – I lighted upon the letter where Winifred recalls lunching at Boulestin’s with Lady Rhondda, Lilian Bayliss[sic], Vera, Margaret West, E.M. Delafield, Rose Macaulay and Sylvia Townsend Warner, complete with the pithy / at times sharp little pen portraits – making me wonder what it must have been like at the Rembrandt Rooms with 130 of such like-minded souls. And of course when a group of people wrote to each other, and about each other, it offers good material!

In 1919 Winifred returned to Somerville to complete her degree. There she met the next key person in her life, Vera Brittain, even though “the immediate reaction of the two women to one another was one of mutual dislike”.[4] A clash at the college Debating Society on “A life of travel is a better education than a life of academic experience” hurt Vera Brittain, clearly still raw from her wartime experience – made worse by a closing quote from Rosalind from the Forest of Arden which (unintentionally) seemed to mock Vera: “I would rather have a fool to make me merry, than experience to make me sad, and to travel for it too”. Winifred realised the problem, they made it up the next term and became lifelong friends.

“They had much in common” including “difficult and powerful parents….In the case of Winifred….. Mrs Holtby – who became the first woman Alderman of the East Riding County Council”, of which a little more later. After graduating Winifred and Vera moved to London, sharing a flat at 58 Doughty Street, a favourite Bloomsbury street of many of this circle.

And of course, particularly relevant to us, Winifred was in at the early days of Time and Tide, and a Director from 1926, and at the time of the dinner pretty well running it due to Lady Rhondda’s poor health, especially in 1932. This workload rankled with Vera, not least because Winifred’s health was even poorer (she had been diagnosed with Bright’s Disease in 1931 and given two years to live), and Vera thought Winifred was being exploited. Winifred it would seem was happy to help, and admired Lady Rhondda – which meant relations between Vera and Lady Rhondda were somewhat cool at this time. Angela V. John, Lady Rhondda’s biographer, writes “Brittain had never accepted Margaret’s friendship with Winifred”.[7] Lady Rhondda herself said “She was almost always happy, full of humour and gaiety, and with a delicious satiric feeling for life…”

Winifred, like Vera, was an ardent feminist, socialist and pacifist, and lectured extensively for the League of Nations Union. She was also a member of Lady Rhondda’s Six Point Group. She was active in the Labour Party and also a staunch campaigner for the unionisation of black workers in South Africa, during which she had considerable contact with Leonard Woolf. She first went to South Africa in January 1926 and was “swept away by the experience”.[8] She wrote home “The situation here is really quite terrible. The stupidity and selfishness of the average South African in face of the colour danger is amazing, and the danger only exists because of this selfish stupidity”.[9]

Like the South African writer Sarah Gertrude Millin, she was also a member of PEN, the writers’ association dedicated to “freedom of expression, peace and friendship, not political debate”, as also were Lady Rhondda and Richard Ellis-Roberts.

When Vera Brittain married George Catlin, Winifred shared their homes in London which clearly caused its own tensions (and Vera and George also had to cope with him being in New York in the early years of the marriage). Winifred became “Auntie” to Shirley Williams and her brother John. At the time of the dinner, Winifred was the successful writer (and having passed the time of her “homing pigeons” – as she termed the time when the rejection letters kept coming back to her – whilst Vera’s to-be-famous Testament of Youth was still in the making (albeit close to publication). In 1932 Winifred wrote to her “What can I say to make you believe in your book as I believe in it?”.[10]

Winifred had one sister, Grace, who married the Hull medic Dr. P Morrison Tolmie, and had two daughters, but Grace died after childbirth on 10th March 1928.[11] [12]

Less than a fortnight before the dinner Winifred’s father was buried in Yorkshire and attendance by the Holtbys on 23rd March may not have been assured. At the dinner Alice Holtby and her adopted sister Edith de Coundouroff are on a table of four, the other two places being listed simply as two guests of Winifred Holtby, presumably reserved and decided close to the time.

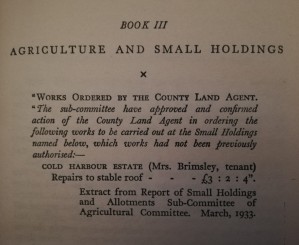

What no-one knew, and possibly not even Winifred, depending on when she wrote her later bestseller South Riding (see below), was the parallel world of Yorkshire facing its own challenges at the time of the dinner. In March 1933, in the story, Alderman Mrs. Beddows, “Winifred’s mother”, “equipped herself for action” as she went off to meet the Cold Harbour colonists. “By the spring of 1933 poverty and despair had wedded out all except the bravest, the most sanguine or the most efficient.” etc etc … there will be no spoilers in The Dinner Puzzle, so read the book!

WHAT WINIFRED (AND OTHERS) DID NEXT

Despite her ill-health Winifred continued to write. In 1931 she had been wooed away by a three-novel contract by the money of Macmillan, away from Jonathan Cape, her previous publisher.[13] Mandoa! Mandoa!, a fictional comedy set in a fictional African state, was the first of the three novels, published in 1933, along with a satire The Astonishing Island (1933). It was followed by a volume of short stories, Truth is Not Sober (1934) and in the same year she also published Women and a Changing Civilization (1934), a feminist survey dedicated to two suffragists, composer Dame Ethyl Smyth and actress and writer Cicely Hamilton, who “did more than write “The March of the Women“.[14] She also inscribed it “To Vera, who taught me to be a feminist”.[15]

But all the time the big one in the offing was South Riding (albeit not to be published by Macmillan and published posthumously). Whilst fiction, it clearly drew upon her knowledge of the political world of West Riding and the work of, amongst others, her mother – who was very opposed to the whole idea. It did after all feature a fictional character who was the first woman to be an Alderman, just as her mother was about to become. Many of these contemporary writers seem to include their friends and acquaintances in their writings, sometimes quite thinly disguised (e.g. E.M. Delafield’s Diary of a Provincial Lady) and their observations emerge of course in the later published diaries and memoirs. EMD, when asked if people complained, responded that people often recognised other people in her Diary but rarely themselves! But Alice Holtby was not happy. The published edition does include a Prefatory Letter to Alderman Mrs. Holtby which opens: My Dear Mother, Because you are a county alderman and because this book concerns a county council, I feel that I owe you a certain explanation and apology. …..and after putting her case Winifred concludes with a lovely tribute to her mother.

Alice Holtby in turn worked with Jean McWilliam to publish the correspondence of “Rosalind” and “Celia” in “Letters to a Friend” in 1937, Collins again the publisher.

Winifred died on 29th September 1935, aged 37. Perhaps one the final dramas of her life involved Harry Pearson, a “rolling stone, with whom she was in love all her life”. She had known him since she was 5, but his war experiences had effectually destroyed him. She wrote to her mother “There can’t be many people who have been in love with the same man for thirty years and not married him in the end”. He proposed to her on her deathbed so she died, happily “believing that she was unofficially engaged”.[20]

Winifred’s Time and Tide family turned out in full for the London tribute to her, the day before her funeral in her home of Driffield, Yorkshire, notably Margaret Rhondda, the Hon. Mrs. Franklin, Vera Brittain, Winifred Cullis, A.E. Harrison, Marion Lyon, Theodora Bosanquet, Clare Leighton, Violet Scott James (who also attended the funeral itself), Joy Scovell, Cicely Hamilton, Noel Brailsford, Lorna Lewis, Margaret West and E.M. Delafield, along with Edith Coundouroff, and all sending floral tributes to Driffield, as also did Alice Mortimer, and Nora and Edith Shackleton.

In 1940 Vera published Testament of Friendship, The Story of Winifred Holtby, in effect the biography of Winifred. Sixty years later a more recent biography was written by Marion Shaw, drawing on a wide range of sources.[21] Winifred wrote poetry too.

BACK TO TOP TABLE

[1] The Guardian

[2] Vera Brittain, Testament of Friendship The Story of Winifred Holtby, Virago Modern Classics edition page 13, 1980.

[3] Vera Brittain, Testament of Friendship The Story of Winifred Holtby, Virago Modern Classics edition p14, 1980.

[4] Shirley Williams, speech at the Winifred Holtby Literary Lunch, Somerville College, 2.10.1985, corrected version, typed unpublished version

[5] Wikipedia, accessed 20.4.2019

[6] Vera Brittain, Testament of Friendship, The Story of Winifred Holtby, Macmillan 1940, Virago edition 2012 p354

[7] Angela V. John, Turning the Tide, Parthian, 2013, p357

[8] Quoting Shirley Williams.

[9] As quoted in Shirley Williams, speech at the Winifred Holtby Literary Lunch, Somerville College, 2.10.1985, corrected version, typed unpublished version

[10] Shirley Williams, speech at the Winifred Holtby Literary Lunch, Somerville College, 2.10.1985, corrected version, typed unpublished version

[11] Hull Daily Mail 11.1.1928

[12] Shirley Williams, speech at the Winifred Holtby Literary Lunch, Somerville College, 2.10.1985, corrected version, typed unpublished version

[13] Vera Brittain, Testament of Friendship, The Story of Winifred Holtby, Macmillan 1940, Virago edition 2012 p353

[14] Winifred Holtby Wikipedia, accessed 20.4.2019

[15] Shirley Williams, speech at the Winifred Holtby Literary Lunch, Somerville College, 2.10.1985, corrected version, typed unpublished version p6

[16] Mark Bostridge, Winifred Holtby’s South Riding, The Guardian, 11.2.2011

[17] Winifred Holtby Wikipedia, accessed 2.4.2019

[18] Picture Source IMDB retrieved April 2019

[19] Picture Source BBC

[20] Shirley Williams, speech at the Winifred Holtby Literary Lunch, Somerville College, 2.10.1985, corrected version, typed unpublished version page 5

[21] Marion Shaw, The Clear Stream: The Life of Winifred Holtby, Virago (1999, republished 2012)